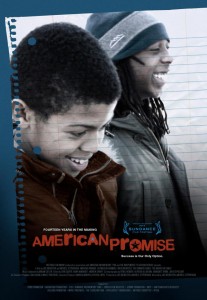

American Promise and the Hazard of Stewarding Black Boys

Last week, I finally watched American Promise on PBS POV. American Promise follows two Black boys – Idris and Seun – and their families as they pass through the Dalton School for primary school and split paths in high school. In so many ways, the film opens an understudied and seldom discussed experience of Black families in elite schools. While we often discuss the fates of Black boys in urban schools, particularly high poverty settings, we talk less often about Black families in well-to-do school settings. What can and should Black parents expect in these settings?

While cameras follow Idris and Seun, the film is more about their parents’ educational and social negotiations than the boys’. Idris’s parents (Joe Brewster and Michele Stephenson) double as central subjects and filmmakers. A moment that stood out to me was Michele Stephenson’s commentary on their choice to send Idris to a historically and predominantly White private school. “Initially I didn’t want to even go to the interview at Dalton. I didn’t want Idris to be part of this elite school that didn’t give him any sense of grounding or sense of self. You know? A bunch of rich white kids disconnected from the larger world that [are] self-involved etc., etc. But going to the school, experiencing commitment to diversity and comparing it to the other schools that I went to, I finally gave in. I can’t say that I regret it. It’s going to hopefully allow him to compete at the top level with his peers.” Stephenson’s analysis is like many Black parents who seek high quality education for their children but simultaneously recognize that schools are often alienating to students of color, at best, and devaluing of them, at worst. Seun’s parents share similar concerns about the issues that they face as they steward young Black males through school.

Both families’ initial reservations seem to be well placed, but when we look at Idris’s and Seun’s paths through Dalton their parental concern didn’t necessarily lead to better outcomes. Seun and Idris were the only two Black boys in the class in primary school and soon were referred to special tutoring services to which none of their classmates were referred. As time passed, both families encountered pressure from the school administration to evaluate their sons for learning disabilities and behavioral problems, and both struggled with peer acceptance. Early on in the film Seun is diagnosed with dyslexia and eventually struggles to stay afloat academically at Dalton, leading him to leave Dalton and attend Benjamin Banneker Academy in Brooklyn for high school (a predominantly Black school with an African-centered school philosophy).

Idris remained at Dalton through high school and had a very different educational experience than Seun. Throughout the film Idris’s parents question the ways Dalton characterizes their son: disruptive, unfocused, hard to manage. His parents highlight his academic acumen but also question his lack of follow through and drive when it comes to academic matters. The school pressures Idris’s parents to test him for ADHD but they resist (it should be noted that Idris’s father is a psychiatrist). In contrast to his parents, Idris wants to be diagnosed because he believes if medicated his test scores may improve, a pattern that he believes has occurred with his classmates. Ultimately he gets assessed and is excited to receive an ADHD diagnosis.

Idris remained at Dalton through high school and had a very different educational experience than Seun. Throughout the film Idris’s parents question the ways Dalton characterizes their son: disruptive, unfocused, hard to manage. His parents highlight his academic acumen but also question his lack of follow through and drive when it comes to academic matters. The school pressures Idris’s parents to test him for ADHD but they resist (it should be noted that Idris’s father is a psychiatrist). In contrast to his parents, Idris wants to be diagnosed because he believes if medicated his test scores may improve, a pattern that he believes has occurred with his classmates. Ultimately he gets assessed and is excited to receive an ADHD diagnosis.

Both Idris and Seun’s experiences reminded me of my educational journey. During my freshman year (and first year) at a similarly elite private school in Connecticut, school administrators encouraged my parents to have me screened for learning issues. Faculty of color at the school privately pulled my parents to the side and informed them that there was a pattern of over-diagnosis of students of color. My parents, excited to have me in such a renowned school, heeded the school administration’s advice to undergo evaluation and ultimately, they were told I had a “learning disability” though no type was ever specified. This led to ” academic accommodations” but also led to teachers treating me differently in the classroom.

The over-diagnosis of Black boys (and to a lesser extent Black girls) with learning disabilities occurs across educational and economic settings. In Inequality in the Promised Land I discuss how parental desires and school staff desires often clash—and what can be done to change that. For many Black parents in well-resourced schools, these dynamics often meant begrudgingly accepting diagnoses they didn’t agree with or being coerced by school cultures that seemed to devalue their children but potentially provided strong academic foundations. This type of trade-off is too common.

In American Promise, we see two families attempt to get the best education for their sons while still dealing with the hazards of race (and to some degree class). The promise of American opportunity will remain unrealized until Black families, as well as poor families, have equal opportunities to reap the benefits of well-resourced schools without suffering pyscho-social consequences along the way.

Filed under: Affirmative Action, Black Men, Campus Life, Class, Education, Gender, General, Inequality in the Promised Land, New York City, Public Policy, Race, Racism, Schools, Sociology, Whiteness, Youth